What You'll Discover

- How microscopic phytoplankton produce more oxygen than all Earth's forests

- Why this sunlit layer supports 90% of all ocean life

- How energy flows through the ocean's most complex food webs

- What survival strategies work in the ocean's most exposed environment

Light as Life Source

Light is the defining feature of the sunlit zone. It enables photosynthesis by microscopic phytoplankton—single-celled algae that drift with currents and form the foundation of nearly every ocean food web. These tiny organisms are incredibly abundant: a single drop of seawater can contain thousands of phytoplankton cells.

The depth of the sunlit zone varies. In clear tropical waters, light can penetrate to 200 meters. In coastal waters rich with sediment and plankton, the zone may end at just 50 meters. The boundary is defined by the compensation depth—where photosynthesis balances respiration, the point where plants produce just enough oxygen to survive but no surplus for growth.

Pause & Predict

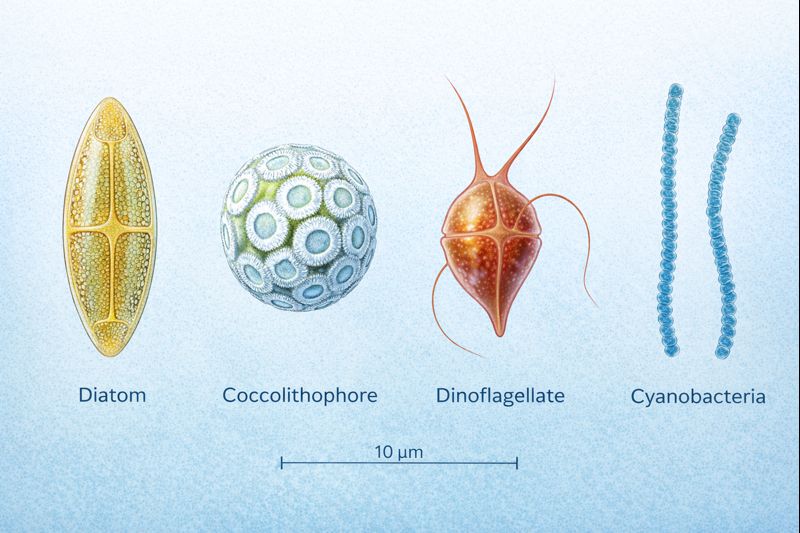

Despite being invisible to the naked eye, phytoplankton are responsible for producing more oxygen than all terrestrial plants combined. These microscopic drifters—including diatoms, cyanobacteria, and dinoflagellates—are the ocean's true powerhouse. A single drop of seawater can contain thousands of these cells, all busily converting sunlight into energy and releasing oxygen as a byproduct. This "invisible forest" is why the sunlit zone is so crucial to life on Earth.

The answer is microscopic floating phytoplankton. While coral reefs, kelp forests, and seagrass meadows are vital ecosystems, they're actually a small fraction of ocean productivity. Phytoplankton — invisible single-celled organisms drifting throughout the sunlit zone — produce the vast majority of ocean oxygen. A single drop of seawater contains thousands of these cells, collectively forming an "invisible forest" more productive than all rainforests combined.

The Floating Forest

Phytoplankton populations bloom and crash with seasonal patterns. In temperate oceans, spring brings explosive growth as winter mixing brings nutrients to the surface and lengthening days provide energy. These blooms can turn water visibly green and are massive enough to be seen from space.

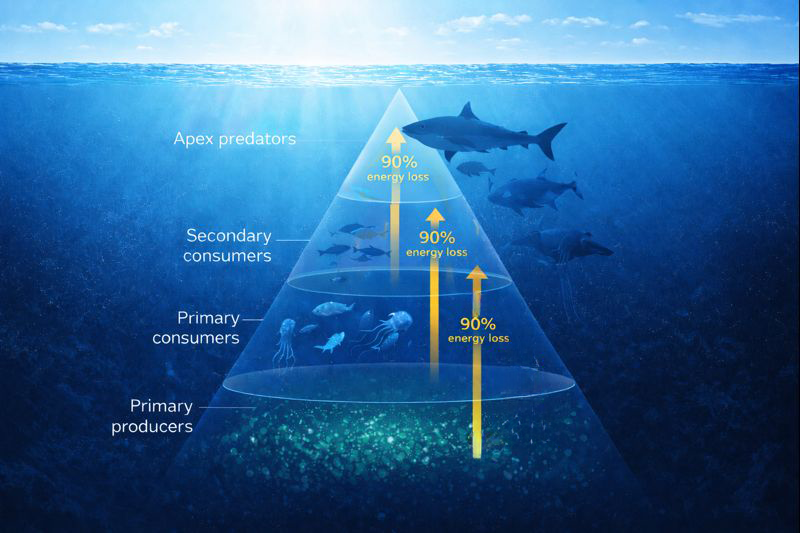

Zooplankton—tiny animals—graze on phytoplankton like cattle in a pasture. This includes copepods (small crustaceans no bigger than a grain of rice) and the larvae of fish and invertebrates. These grazers are in turn eaten by small fish, which are eaten by larger fish, and so on up the food chain to apex predators like tuna, sharks, and whales.

The Food Web

The sunlit zone's food web is complex and interconnected. Energy flows from phytoplankton through multiple trophic levels, but with significant loss at each step—roughly 90% of energy is lost as it moves up the food chain through metabolism and waste.

Despite its abundance of life, the sunlit zone presents challenges. There's nowhere to hide in the open water. Predators can attack from any direction. Many species have evolved countershading—dark on top, light below—to blend with the light from above and darkness below. Others form schools for protection, or have evolved speed and agility to escape.

Survival Strategies

Life in the sunlit zone has evolved diverse strategies for the unique challenges of this illuminated, exposed environment.

Apply It

You're a marine biologist designing a new species for the sunlit zone. It's a small fish, about 10cm long, that feeds on zooplankton. Which survival strategy would help it most?

Bioluminescence is brilliant—but not here! In the sunlit zone, there's already plenty of light, so producing your own doesn't help with camouflage. In fact, it might make you more visible to predators. Bioluminescence is much more useful in the twilight and midnight zones where light is scarce. Great thinking about deep-sea adaptations though!

Countershading is one of the most effective strategies in the sunlit zone! A dark back makes the fish blend with darker water below when viewed from above (by birds or surface predators), while the light belly makes it blend with bright surface light when viewed from below (by predators in deeper water). This simple color pattern provides 360-degree camouflage. Many successful sunlit zone species—from sardines to sharks—use this strategy.

An armored shell provides protection, but it comes with major downsides in the sunlit zone. The extra weight makes it harder to stay buoyant and reduces swimming speed—critical for escaping fast predators like tuna or mako sharks. In the exposed, three-dimensional environment of open water, speed and agility usually beat heavy armor. That said, some species like boxfish do use limited armor successfully by combining it with toxins!

Schooling is a brilliant choice! When thousands or millions of small fish swim together in coordinated patterns, they create confusion for predators—a phenomenon called the "confusion effect." The predator has trouble focusing on a single target. Schools can also make the group appear larger and more intimidating. Plus, many eyes mean better early warning of danger. Species like sardines, anchovies, and herring have mastered this strategy and become some of the most abundant fish in the ocean!

The Biological Pump

The sunlit zone doesn't just produce food—it regulates Earth's climate. Through a process called the biological pump, carbon captured by photosynthesis in surface waters is transported to the deep ocean when organisms die and sink.

"The sunlit zone is Earth's largest carbon capture system—phytoplankton draw down billions of tonnes of CO annually, much of which ends up sequestered in the deep sea."

This carbon pump is one of the ocean's most important services to the planet. Without it, atmospheric CO would be significantly higher. Climate change threatens to disrupt this system by warming surface waters, strengthening stratification, and reducing the nutrient mixing that fuels phytoplankton growth.

Connection Challenge

Explain how phytoplankton help regulate Earth's climate. Tap key phrases below to build your answer:

Phytoplankton absorb CO from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, converting it into organic matter. When they die, they sink to the deep ocean, effectively removing that carbon from the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years—acting as a massive natural carbon capture system.

Your answer might have used different phrases and that's perfect! The key is understanding how these microscopic organisms have planet-scale climate impacts.

Diel Vertical Migration: The Greatest Journey on Earth

Every single day, the largest animal migration on Earth takes place in the ocean's waters—and most people have never heard of it. Diel vertical migration (DVM) is the daily journey of billions of organisms between the sunlit zone and deeper waters, driven by the cycle of day and night.

As the sun sets, an astonishing procession begins. Zooplankton, small fish, squid, jellyfish, and countless other creatures rise from the twilight zone—sometimes traveling 400 to 800 meters vertically—to feed in the food-rich surface waters under cover of darkness. By dawn, they descend again to the relative safety of the deep, where light is too dim for visual predators to hunt effectively.

The scale is staggering. Scientists estimate that biomass equivalent to the weight of several billion people makes this journey twice a day. The migration is so massive that sonar operators initially mistook the dense layer of animals for the seafloor itself—a phenomenon they called the "deep scattering layer."

The vertical migration represents a fundamental trade-off: risk versus reward. The sunlit zone offers abundant food but also exposes organisms to visual predators. The twilight zone offers darkness and safety but little food. By migrating, organisms get the best of both—feeding at night when predators can't see them, then retreating to safety during the day.

DVM has profound impacts on ocean ecology and global carbon cycling. These migrating organisms are essentially a biological conveyor belt, transporting carbon from the surface to depth. They feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton in the sunlit zone, then excrete waste and respire CO in deeper waters. When they die, their bodies sink, carrying carbon to the deep sea where it remains sequestered for centuries.

This "active transport" of carbon by migrating organisms significantly enhances the ocean's biological pump, helping regulate Earth's climate. Research suggests that diel vertical migration may transport as much as 1 billion tonnes of carbon to the deep ocean annually—a climate service worth understanding and protecting.

Check Your Understanding

Based on what you just read about diel vertical migration, which statements are accurate? (Select all that apply)

DVM is indeed the largest daily migration on Earth, with billions of organisms ascending at dusk to feed safely at night. This migration transports roughly 1 billion tonnes of carbon annually to the deep ocean. While moon phase can influence some marine behavior, DVM is primarily driven by the daily light cycle, not lunar phases.

Connections to the Deep

Through diel vertical migration and the sinking of organic matter, the sunlit zone is intimately connected to the ocean's depths. These connections make the ocean a single, integrated system rather than isolated layers. What happens in the sunlit zone affects the entire ocean—and what happens in the deep can, in turn, influence surface waters through upwelling and nutrient recycling.

The sunlit zone may be thin, but its influence extends throughout the ocean. It's the source of almost all food, the engine of the carbon cycle, and the birthplace of most marine life. Understanding this zone is fundamental to understanding the ocean itself.

Threats and Changes

The sunlit zone faces multiple pressures. Warming temperatures are changing species distributions. Ocean acidification threatens shell-forming plankton. Pollution accumulates in surface waters. Overfishing has removed many top predators. And nutrient runoff creates dead zones where oxygen is depleted.

Perhaps most concerning, the base of the food web—the phytoplankton—may be declining. Some studies suggest phytoplankton populations have dropped 40% since 1950, though the data remains debated. If true, the implications ripple through every ocean ecosystem and Earth's climate system.

Knowledge Check

Validate your understanding of the sunlit zone