🎯 What You'll Discover

Essential insights into coral reefs

Builders of Complexity

Understand how tiny coral polyps construct Earth's largest living structures and create the most biodiverse marine ecosystems.

Symbiotic Partnerships

Explore the intimate relationship between corals and zooxanthellae algae—a partnership that powers entire reef systems.

Survival in Nutrient Deserts

Discover how reefs thrive in crystal-clear tropical waters through efficient nutrient recycling and specialized adaptations.

Reefs Under Pressure

Learn why coral reefs face unprecedented threats from climate change, ocean acidification, and human impacts.

The Reef Paradox

Coral reefs are the most productive, biodiverse ecosystems in the ocean — yet they thrive in water so nutrient-poor it's essentially a marine desert. How can the richest habitat grow in the poorest water?

This paradox defines reef biology. Where tropical seas are typically clear and blue precisely because they lack the nutrients that support plankton blooms, coral reefs explode with life — an estimated 25% of all marine species are associated with reefs (using them for habitat, feeding, or reproduction) despite reefs occupying less than 0.1% of the ocean floor.

The answer lies in partnership. Coral reefs are not simply habitats — they are vast, interlocking networks of symbiosis, where organisms share resources so efficiently that almost nothing escapes. The reef runs on sunlight and recycling.

Coral reefs achieve rainforest-level productivity in desert-level nutrients. The secret: they don't need external nutrients because they barely leak internal ones. Energy and matter cycle organism-to-organism with extraordinary efficiency. What enters the system stays in the system.

Understanding this paradox is the key to understanding why reefs are both so productive and so fragile — why they've built entire archipelagos over millions of years, and why they're now collapsing in decades.

Pause & Predict

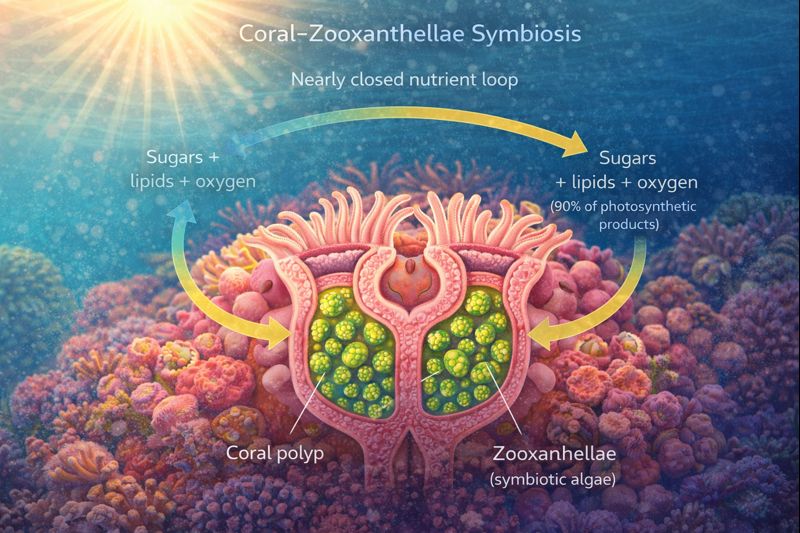

The coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis is the key to solving the nutrient paradox. Billions of algae live inside coral tissues, photosynthesizing and transferring up to 90% of their products to the coral. The coral provides CO₂, nutrients from waste, and shelter. This creates an almost perfectly closed loop where nutrients cycle internally with minimal loss. Unlike most ecosystems that depend on external nutrient inputs (upwelling, rivers, detritus), reefs run on internal recycling. The partnership allows rainforest-level productivity in desert-level conditions—the defining paradox of coral reefs.

The Stage

Coral reefs exist in a narrow band of conditions — a Goldilocks zone defined by the needs of the coral-algae symbiosis that builds them.

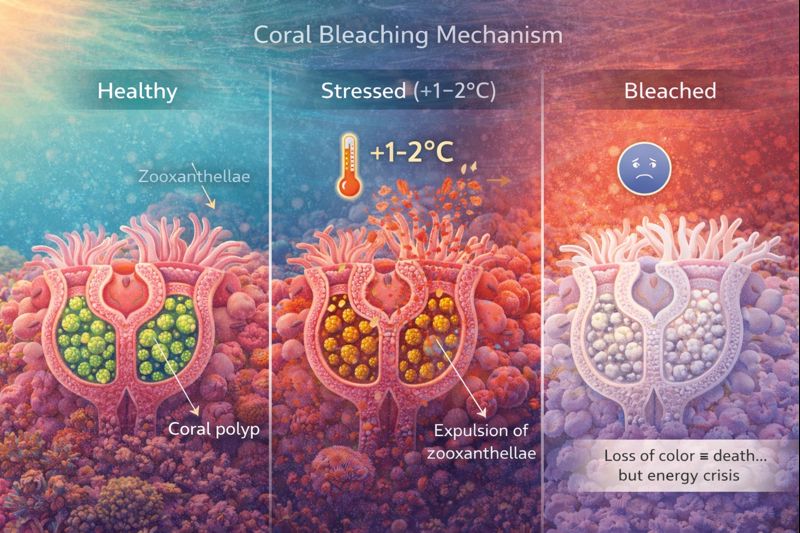

Warm: Reef-building corals need water between 23-29°C. Below this, growth slows to nothing. Above it — even by just 1-2°C — the symbiosis that powers the reef breaks down.

Shallow: Sunlight must reach the bottom. Most reef growth occurs above 30 meters, though some "mesophotic" reefs extend to 150 meters in exceptionally clear water.

Clear: Clarity comes from nutrient poverty. Low nutrients mean low plankton, which means light penetrates deep. High nutrients would feed algae that smother corals.

Stable: Corals tolerate narrow ranges. Temperature swings, salinity shifts, or sediment pulses can stress or kill them. The tropical belt provides the stability they need.

Heat Flow defines where reefs can exist — the warm tropical belt. Energy Flow makes the symbiosis possible — abundant sunlight powers the algae that power the corals. Nutrient Flow shapes which waters stay clear enough for reefs — paradoxically, reefs need nutrients to be elsewhere.

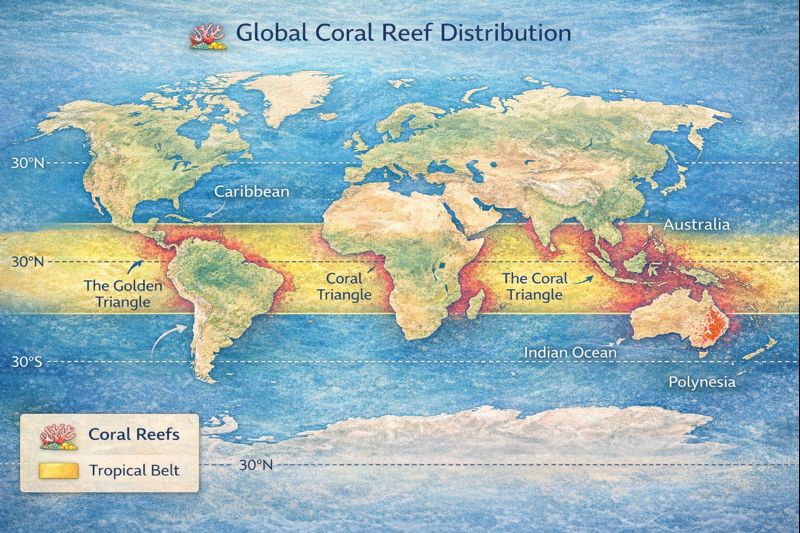

Geography: The Indo-Pacific holds 75% of reef area, centered on the Coral Triangle (Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea). The Caribbean, Red Sea, and scattered Pacific atolls hold the rest. Nearly all lie within 30° of the equator, with notable exceptions like Bermuda (32°N), where the warm Gulf Stream sustains reef growth at unusually high latitude.

The Foundation

Every reef is built on a partnership so tight it functions as a single organism: the coral-algae symbiosis.

Reef-building corals are animals — colonies of tiny polyps, each a few millimeters across, related to jellyfish and anemones. But inside their tissues live billions of single-celled algae called zooxanthellae. This union is the engine of the reef.

By day, zooxanthellae photosynthesize, capturing sunlight and converting it to sugars and lipids. They transfer up to 90% of this photosynthetically fixed carbon to their coral hosts — a subsidy so enormous that corals barely need to catch food during the day. In return, corals provide shelter, carbon dioxide from respiration, and nutrients from their waste.

The coral-algae symbiosis is why reefs solve the nutrient paradox. Instead of depending on external nutrient supplies like most ecosystems, reefs run on internal recycling. The algae photosynthesize; the coral metabolizes; the waste feeds the algae; nothing escapes. The system is nearly closed.

Note: While symbiosis provides most of their carbon, corals are also capable heterotrophs — extending polyps at night to capture zooplankton. This supplemental feeding becomes crucial during and after bleaching events when the symbiosis is compromised.

This tight coupling explains both the reef's productivity and its vulnerability. When the partnership works, corals can build massive structures over thousands of years. When it breaks — as happens during heat stress — corals lose their energy source, their color, and often their lives.

Other primary producers contribute to the reef's foundation:

Apply It

While bleaching is extremely serious, corals don't die instantly. They have energy reserves and can increase heterotrophic feeding (catching zooplankton at night). If heat stress is brief (days to weeks), corals can survive and reacquire algae. However, prolonged bleaching (months) does lead to starvation and death. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals after months of stress.

Losing zooxanthellae means losing up to 90% of the coral's energy input—catastrophic but not instantly fatal. Corals have energy reserves and can increase heterotrophic feeding (catching zooplankton). If stress is brief, they can survive and reacquire algae when conditions improve. But prolonged bleaching (months) exhausts reserves, compromises immune systems, and leads to disease and death. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals after extended stress. The partnership that makes reefs productive also makes them vulnerable to temperature disruption.

Skeleton building does slow dramatically during bleaching, but the MOST immediate consequence is energy loss. Without zooxanthellae providing up to 90% of metabolic needs, corals face starvation. This energy crisis is what makes bleaching so dangerous. If brief, corals can survive on reserves and heterotrophic feeding. But extended bleaching (months) leads to death—30% of Great Barrier Reef corals died in the 2016 event. The skeleton issue is secondary to the energy crisis.

Reproduction is indeed compromised during bleaching—stressed corals often skip spawning. But the MOST immediate consequence is energy loss. Losing zooxanthellae means losing up to 90% of metabolic input. Corals have reserves and can increase feeding, so brief bleaching (weeks) may not be fatal. But prolonged stress (months) causes starvation, disease, and death—the 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals. The reproductive issue is real but secondary to the energy crisis.

The Cast

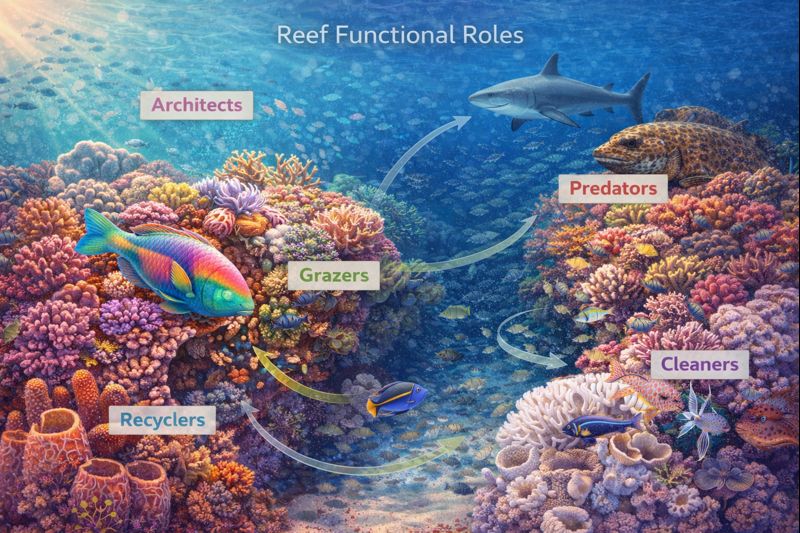

A coral reef is a city, and every city needs its workers. Architects build structure. Grazers maintain surfaces. Predators regulate populations. Cleaners keep everyone healthy. Decomposers recycle the dead.

These organisms create the three-dimensional framework — every crevice, overhang, and hole becomes habitat for something else.

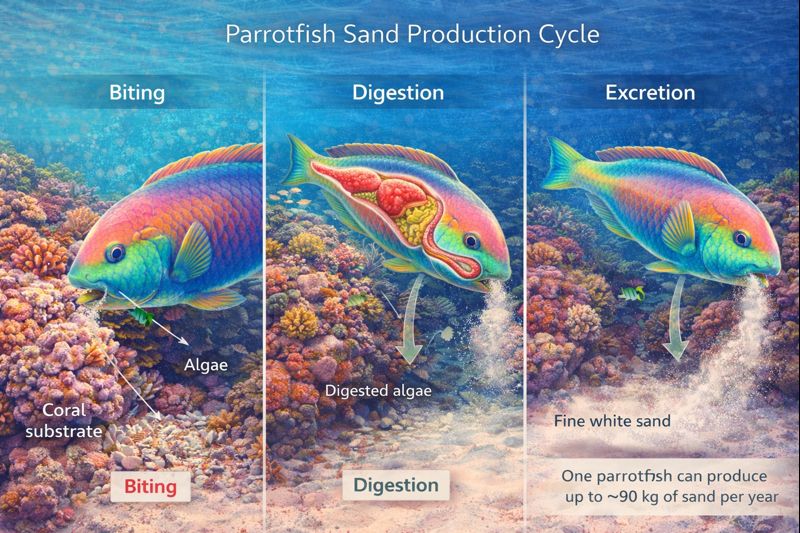

Without grazers, algae would overgrow and smother corals. These herbivores maintain the balance that allows coral dominance.

Apex and mesopredators structure the food web, preventing any single species from dominating and maintaining diversity through top-down control.

Reefs have more documented symbioses than any other ecosystem. Cooperation is as important as competition.

Filter feeders and detritivores process water and waste, capturing particles and recycling nutrients back into the system.

Remove any guild and the system shifts. When disease killed Caribbean sea urchins (Diadema) in 1983, algae overgrew reefs within months. When sharks are fished out, mesopredator populations explode, cascading through the food web. The cast is not just a list — it's a set of interlocking dependencies.

Connection Challenge

Build a complete explanation of the coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis. Click phrases to construct your answer, demonstrating how this partnership allows reefs to thrive in nutrient-poor water.

The coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis creates a nearly closed nutrient loop that solves the paradox of high productivity in low-nutrient water. Millions of zooxanthellae algae live protected inside coral tissues. The coral provides them with CO₂ from respiration and nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus) from its metabolic waste. In return, zooxanthellae photosynthesize using sunlight, producing sugars, lipids, and oxygen—they transfer up to 90% of these products directly to the coral.

This massive energy subsidy means corals barely need external food during the day. The photosynthesis also helps corals deposit calcium carbonate skeleton faster. Crucially, the algae use the coral's waste while the coral uses the algae's products—nutrients cycle internally with minimal loss. Unlike ecosystems dependent on external inputs (upwelling, rivers, detritus), reefs run on internal recycling.

This explains how reefs achieve rainforest-level productivity in desert-level nutrients. It also explains their fragility: when the partnership breaks (heat stress → bleaching), the entire system collapses.

Your answer might emphasize different aspects—that's excellent! The key is understanding the bidirectional exchange and closed nutrient loop.

Life Strategies

Every reef organism has solved the challenges of tropical ocean life. These solutions — repeated and refined over millions of years — reveal what it takes to thrive here.

Finding Food in Nutrient-Poor Water

The reef's signature solution is internal symbiosis — farming algae inside your own tissues. Corals do it. Giant clams do it. Some nudibranchs steal chloroplasts from their food and photosynthesize themselves.

Other strategies include cleaning stations (guaranteed food for cleaners), mucus nets (corals trap particles in sticky secretions), and extreme filter efficiency (sponges process thousands of liters daily, extracting bacteria and dissolved organics invisible to other feeders).

Avoiding Death in a Crowded City

With nowhere to run, reef organisms have evolved remarkable defenses:

Camouflage: Octopuses match coral texture in seconds. Stonefish are invisible on rubble. Pygmy seahorses are indistinguishable from their gorgonian hosts.

Venom: Lionfish, stonefish, cone snails, blue-ringed octopus — the reef is a pharmacy of toxins.

Armor: Boxfish skeletons, porcupinefish spines, sea urchin tests.

Mimicry: The fangblenny mimics cleaner wrasses to approach fish — then bites them and flees.

Reproduction in a Vast, Dilute Sea

Finding a mate in the ocean is hard. Reef organisms have evolved solutions ranging from synchrony to intimacy:

On specific nights each year — cued by moon phase, temperature, and sunset timing — hundreds of coral species release eggs and sperm simultaneously. The sea becomes a blizzard of gametes, overwhelming predators by sheer abundance. Larvae drift for days to weeks before settling, connecting distant reefs across oceanic distances.

Regional note: Mass spawning synchrony is most dramatic on the Great Barrier Reef and in the Coral Triangle. Caribbean reefs show more staggered spawning across species and months, though synchrony within species still occurs.

Brooding: Some corals retain larvae internally, releasing them ready to settle. Less risky, but less dispersal.

Hermaphroditism: Many reef fish can change sex. Clownfish are born male; the dominant individual becomes female. Groupers start female, become male. When you might never find another of your species, flexibility helps.

Check Understanding

Overfishing is indeed a major LOCAL stressor. Removing herbivorous fish allows algae to overgrow corals, especially after bleaching. But the PRIMARY global threat is ocean warming. Rising temperatures cause mass bleaching events—when water heats just 1-2°C above normal for weeks, corals expel their zooxanthellae and often die. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals. Warming acts at global scale and is accelerating. Local stressors like overfishing compound warming's impacts, but warming is now the dominant threat. Half of global reef cover has been lost since 1950, mostly from warming-driven bleaching.

Ocean warming is now the PRIMARY threat to reefs worldwide. When temperatures rise even 1-2°C above normal for weeks, corals bleach—expelling their zooxanthellae and losing up to 90% of their energy source. Extended bleaching leads to starvation and death. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef event killed 30% of corals. Mass bleaching events are increasing in frequency and severity as oceans warm. While local stressors (overfishing, pollution, sedimentation) are serious and compound warming's effects, warming acts at global scale and is accelerating. Half of reef cover lost since 1950. Current trajectories suggest 90%+ loss by 2050 without radical intervention.

Nutrient pollution is indeed a serious LOCAL problem. Excess nutrients (from agriculture, sewage) fuel algal growth that smothers corals. But the PRIMARY global threat is ocean warming. Mass bleaching events—when temperatures rise 1-2°C for weeks—cause corals to expel zooxanthellae and often die. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals. Warming acts globally and is accelerating. Local stressors like pollution compound warming but don't drive global reef decline on their own. Half of reef cover lost since 1950, mostly from warming-driven bleaching.

Ocean acidification is indeed a serious and accelerating threat. As CO₂ dissolves in seawater, it reduces carbonate ions needed for skeleton building. This makes growth slower and structures weaker. But the PRIMARY current threat is ocean warming. Mass bleaching events—when temperatures rise 1-2°C for weeks—cause immediate widespread mortality. The 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching killed 30% of corals in months. Acidification is a slower process but will compound warming's effects. Both are driven by CO₂ emissions. Together they create a perfect storm for reefs. Half of reef cover lost since 1950, mostly from warming-driven bleaching.

Under Pressure

The same sensitivity that makes coral reefs possible makes them vulnerable. The narrow conditions they require are shifting — in some places, disappearing.

When water temperatures exceed corals' tolerance — often just 1-2°C above normal summer maximum — the coral-algae symbiosis breaks down. Corals expel their zooxanthellae, losing their color and their energy source. If heat persists, they starve.

Global bleaching events (1998, 2010, 2016-17, 2023-24) have killed vast swaths of reef. The 2023-24 event affected over 80% of global reef area — the most severe on record.

Rising ocean temperatures are a direct consequence of Heat Flow disruption — the ocean absorbing excess warmth from greenhouse gas emissions. What once buffered climate now stresses the ecosystems that depend on stability.

As oceans absorb CO₂, pH drops. Lower pH means less available carbonate for skeleton-building. Corals must spend more energy to calcify. Below certain thresholds, skeletons dissolve faster than they're built. Reefs could shift from net growth to net erosion.

The ocean's role as carbon sink — absorbing 25-30% of human CO₂ emissions — creates the chemistry change that threatens calcifiers. The service the ocean provides to climate regulation comes at a cost to the organisms that build reefs.

Local Stressors

Overfishing: Remove grazers, and algae smother corals. Remove predators, and trophic cascades destabilize the food web.

Nutrient pollution: Sewage and agricultural runoff fertilize algae, shifting the competitive balance away from corals.

Sedimentation: Coastal development, deforestation, and dredging send sediment onto reefs, smothering corals and blocking light.

Physical damage: Anchors, dynamite fishing, and careless tourism directly destroy reef structure.

Local stressors weaken corals' ability to survive climate stress. A reef degraded by overfishing and pollution has less capacity to recover from bleaching than a healthy reef. This is the conservation lever: we can't quickly stop ocean warming, but we can reduce local pressures — giving reefs their best chance to persist through the climate transition.

Why Coral Reefs Matter

Biodiversity: An estimated 25% of all marine species are associated with reefs at some life stage — for habitat, feeding, nursery, or reproduction. The Coral Triangle alone holds 76% of reef-building coral species, 37% of reef fish species. Reefs are evolution's masterpiece — and a genetic library we've barely opened.

Food security: Reef fish provide protein for over 500 million people, mostly in coastal developing nations. Subsistence fishing is often invisible in statistics but essential for survival.

Coastal protection: Reef structure dissipates wave energy — reducing wave height by 97% on average. Without reefs, storms cause more flooding; erosion accelerates. This service is worth billions annually.

Economic value: Reef tourism generates $36 billion/year globally. For many island nations, it's the economic backbone.

Pharmaceutical potential: Reef organisms produce novel compounds for defense and competition. Cone snail toxins have yielded painkillers; sponge compounds show anticancer activity.

The stakes are existential. Under high-emission scenarios, 70-90% of existing coral reefs may be functionally gone by 2050. This isn't just ecological loss — it's the collapse of food systems, livelihoods, and coastal defenses for hundreds of millions of people.

Sources: IPCC Special Report on Oceans and Cryosphere, 2019; Spalding et al., Science, 2017; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2017; Reaka-Kudla, 1997 (biodiversity estimates)

Knowledge Check

Validate your understanding of coral reef ecosystems

Systems Connection

Every flow you studied in Ocean Systems shapes reef existence. Here's how they converge:

What You've Learned

- Coral reefs solve the "nutrient paradox" through internal symbiosis and tight nutrient recycling

- The coral-algae partnership (zooxanthellae) is the foundation — an energy subsidy that powers the entire ecosystem

- Reef organisms form an interlocking cast: architects, grazers, predators, cleaners, recyclers — remove any guild and the system shifts

- Life strategies include symbiosis, chemical defense, camouflage, and mass spawning synchrony

- Thermal stress, acidification, and local stressors are compounding threats — but local management remains the key lever

- Reefs support 500+ million people directly — their loss is humanitarian, not just ecological