🎯 What You'll Discover

Essential insights into kelp forests

Underwater Jungles

Explore how giant kelp creates three-dimensional forests that rival terrestrial rainforests in productivity and biodiversity.

Fastest Growing Organisms

Understand how kelp can grow up to 60cm per day and reach 45 meters tall—matching the growth rates of bamboo.

Keystone Species Dynamics

Discover how sea otters, urchins, and kelp form a classic example of trophic cascade effects in marine ecosystems.

Temperate Powerhouses

Learn why cold, nutrient-rich waters create ideal conditions for these remarkably productive ecosystems.

The Kelp Paradox

Kelp has no roots, no wood, no rigid skeleton — yet it builds forests up to 60 meters tall that rival rainforests in productivity. How does a seaweed become a sequoia?

The answer lies in a fundamentally different engineering strategy. Where trees fight gravity with rigid trunks, kelp surrenders to water and uses it. Where terrestrial forests draw nutrients through roots, kelp absorbs everything through its surface. Where land plants grow slowly and persist for decades, kelp grows explosively and regenerates constantly.

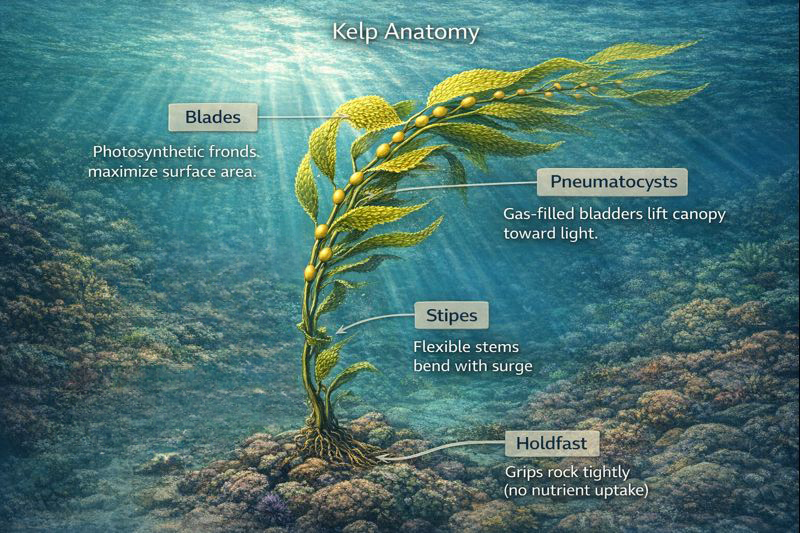

Giant kelp can grow up to 60 cm per day under ideal conditions (typically 30-40 cm on average) — among the fastest growth rates of any organism on Earth. It accomplishes this without any internal support structure. The secret: gas-filled bladders (pneumatocysts) float the canopy toward light, while flexible stipes bend with currents instead of resisting them. Kelp doesn't fight the ocean — it flows with it.

Kelp forests are also the ecological inverse of coral reefs. Where reefs need warm, clear, nutrient-poor water, kelp demands cold, turbulent, nutrient-rich conditions. Understanding kelp means understanding a completely different solution to the challenge of building an underwater ecosystem.

Pause & Predict

Kelp's extraordinary growth depends on cold, nutrient-rich water. Coastal upwelling brings deep water loaded with nitrates and phosphates to the surface. Unlike terrestrial plants limited by soil nutrients, kelp bathes in this nutrient soup while also accessing unlimited CO2 from seawater. The giant blade surface area maximizes light capture. Cold water (8-20°C) is crucial—it holds more dissolved nutrients and gases than warm water. This combination—abundant nutrients, constant water flow delivering resources, year-round growing season in temperate zones, and massive photosynthetic surface area—allows kelp to add 60cm daily during peak growth. This makes kelp one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth, rivaling tropical rainforests despite much lower biodiversity.

The Stage

If coral reefs are tropical cities, kelp forests are cold-water cathedrals. Every condition that defines them is opposite to reef requirements.

Cold: Most kelp species thrive between 5-20°C. Above 20°C, many begin to suffer; prolonged warmth kills them outright. Kelp forests hug cold coastlines and vanish in the tropics.

Nutrient-rich: Kelp grows fast — some species add 30-60 cm per day. That velocity requires constant nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron delivered by upwelling currents and cold-water circulation.

Rocky substrate: Unlike seagrasses, kelp can't root in sand. It grips rock with a holdfast — an anchor that provides attachment but absorbs nothing. All nutrition comes directly from the water.

Turbulent: Kelp forests thrive in surge and swell. Currents deliver nutrients, carry away spores, and create the constant flow kelp is engineered to handle. The apparent chaos is actually the engine.

Nutrient Flow determines where kelp forests can exist — upwelling zones and cold eastern boundary currents deliver the fertility kelp demands. Water Flow brings those nutrients and disperses reproductive spores. Heat Flow sets the thermal boundaries — kelp exists where warm currents don't reach.

Geography: Temperate coastlines worldwide — California to Alaska, Chile, South Africa, southern Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Korea, Norway, the British Isles. Some species extend into sub-Arctic (northern Norway, Iceland) and sub-Antarctic waters. Anywhere cold, nutrient-rich water meets rocky coast.

The Foundation

Giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) is the icon — reaching 60 meters, growing up to 60 cm per day, visible from space. But it's not a plant. Kelp is a brown alga — a stramenopile, more closely related to diatoms than to any terrestrial tree.

Its structure solves an engineering problem unique to the ocean: how to reach sunlight from the seafloor without wood or roots.

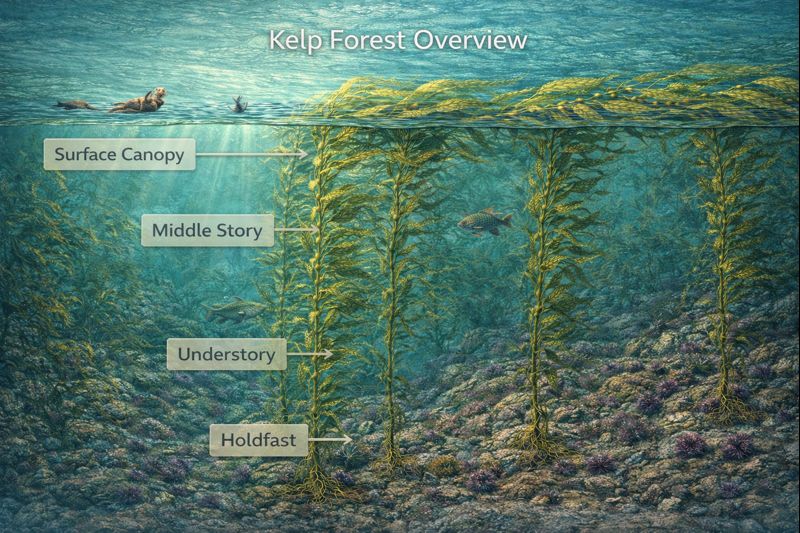

This architecture creates a three-dimensional forest — a layered vertical habitat from seafloor to surface. The holdfast zone, understory, mid-canopy, and surface canopy each host different communities, different light levels, different flow regimes.

Unlike coral reefs, which recycle nutrients internally, kelp forests are throughput systems — constantly importing nutrients from upwelling and exporting organic matter as drift kelp, dissolved compounds, and sinking detritus. The forest persists not through durability but through constant regeneration.

Productivity: Kelp forests are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth — fixing 500-1500 grams of carbon per square meter per year, comparable to tropical rainforests. This productivity cascades through the food web and beyond: drift kelp feeds beaches, deep-sea communities, and ecosystems far from the forest itself.

Kelp and seagrass both form underwater "meadows" and "forests," but they're fundamentally different organisms. Seagrasses are flowering plants that returned to the ocean ~100 million years ago — they have roots, produce seeds, and absorb nutrients from sediment. Kelp is an alga that never left the water — it has no roots, no flowers, and absorbs everything through its surface. They occupy different habitats and play different ecological roles.

Apply It

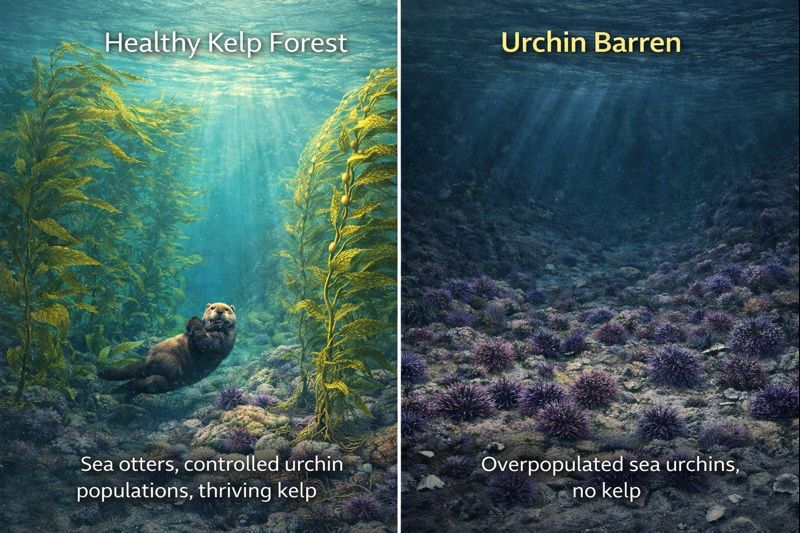

While kelp grows incredibly fast (up to 60cm/day), it cannot outgrow unchecked urchin grazing. Urchins are voracious kelp predators—a single urchin can consume several kg of kelp per month. Without otters controlling their population, urchins multiply exponentially. They graze kelp holdfasts (roots), toppling entire plants. The forest collapses into an "urchin barren"—a desolate seafloor covered in urchins and encrusting algae, virtually devoid of kelp. This alternative stable state can persist for decades. Real example: When sea otters were hunted to near-extinction in the 1800s, vast kelp forests collapsed. Recovery requires either otter reintroduction or urchin removal.

Exactly right. Without otters to control them, sea urchin populations explode. Urchins are voracious kelp predators—each can consume several kg per month. They target kelp holdfasts (the "roots"), toppling entire plants. Kelp cannot regrow fast enough to keep pace with unchecked grazing. The forest collapses into an "urchin barren"—a desolate seafloor carpeted with urchins and encrusting coralline algae, virtually devoid of kelp. This is an alternative stable state that can persist for decades because urchins prevent any kelp recruitment. Real-world example: When sea otters were hunted nearly to extinction in the 1800s, vast Pacific kelp forests collapsed. Recovery requires otter reintroduction or manual urchin removal. This trophic cascade demonstrates how keystone predators control entire ecosystems.

In theory, other predators (sunflower stars, lobsters, certain fish) could control urchins. But in practice, this rarely happens fast enough or effectively enough. Urchin populations explode too quickly, and alternative predators don't fill the otter niche completely. The result? Kelp forest collapse into "urchin barrens"—desolate seafloors covered in urchins and coralline algae with almost no kelp. This alternative stable state can persist for decades. Only otter reintroduction or manual urchin removal reliably restores kelp. The 1800s sea otter hunting caused massive kelp loss that persisted until otter recovery programs in the 1900s. Ecosystems don't always self-correct—trophic cascades can lock in degraded states.

While some kelp species do have mild chemical defenses, evolution operates over thousands of generations—far too slowly to respond to sudden urchin explosions. Kelp cannot evolve new defenses in the years or decades timescale of otter loss. The result is forest collapse into "urchin barrens"—desolate seafloors covered in urchins with virtually no kelp. Urchins graze faster than kelp can regrow, targeting holdfasts and toppling entire plants. This alternative stable state persists for decades without intervention. The 1800s sea otter hunting caused massive kelp loss that lasted until otter recovery programs. Kelp's only "adaptation" is its fast growth—but even 60cm/day cannot outpace unchecked urchin grazing.

The Cast

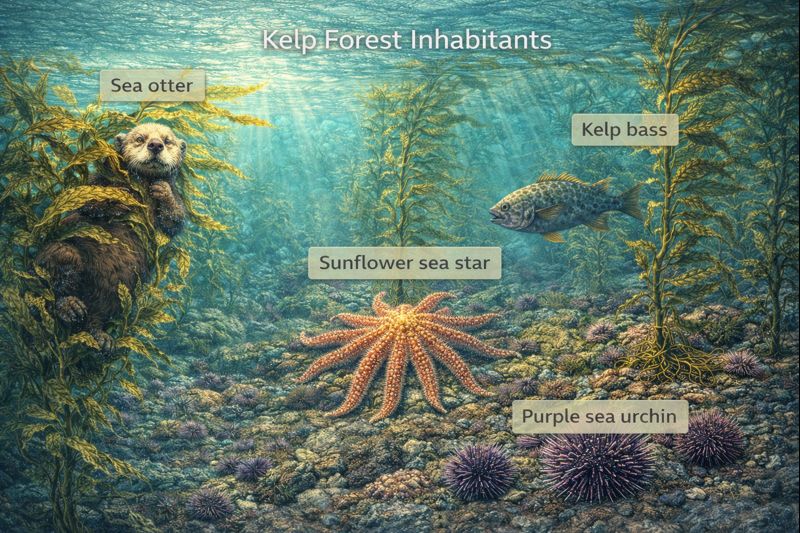

A kelp forest is structured by a single relationship — the predator-grazer-producer cascade that defines whether kelp thrives or collapses.

No discussion of kelp forests is complete without the animal that revealed what "keystone species" means.

Sea otters eat sea urchins. Sea urchins eat kelp. When fur traders hunted otters to near-extinction in the 18th-19th centuries, urchin populations exploded, devouring kelp forests and leaving behind "urchin barrens" — underwater deserts of bare rock and grazing urchins.

When otters returned through protection and reintroduction, urchin populations dropped and kelp forests recovered. This cascade became the textbook example of top-down ecosystem control.

Estes & Palmisano, 1974 — the paper that launched trophic cascade research

Different kelp species create different forest structures, from towering canopies to dense understories.

Grazer populations determine whether kelp thrives or collapses. Controlled grazing recycles nutrients; unchecked grazing creates barrens.

Predators keep grazer populations in check, preventing the shift to urchin barrens.

The floating kelp canopy hosts its own specialized community — a habitat within the habitat.

A single giant kelp holdfast can harbor over 100,000 individual invertebrates — brittle stars, polychaete worms, amphipods, isopods, small crabs, snails, tunicates. The anchor is an ecosystem unto itself.

Connection Challenge

Build a complete explanation of how kelp forests create habitat. Click phrases to construct your answer, demonstrating how kelp's structure supports entire ecosystems.

Kelp forests create habitat through their unique three-dimensional architecture. Individual kelp plants grow from holdfasts anchored to rocky substrate, extending blades up to 45 meters to form a dense surface canopy. This creates vertical structure from seafloor to surface—unlike most marine habitats which are two-dimensional. The canopy slows water flow and reduces wave energy, creating calmer conditions beneath.

This physical structure provides shelter for hundreds of species across multiple depth zones. The canopy itself houses fish seeking surface food and protection. Mid-water zones support drifting invertebrates and hunting predators. The seafloor holdfast community includes anemones, urchins, and detritus feeders. Kelp also produces oxygen through photosynthesis and exports organic matter to surrounding ecosystems.

The forest functions as a biodiversity hotspot—temperate zone equivalent of tropical reefs. It's critical nursery habitat for juvenile rockfish, lingcod, and other commercially important species. The structure buffers coastlines from storm damage and wave erosion. Kelp forests support entire food webs from microscopic diatoms to apex predators like sharks and otters. When forests collapse into urchin barrens, this entire community disappears.

Your answer might emphasize different aspects—that's excellent! The key is understanding how kelp's physical structure creates ecological value.

Life Strategies

Kelp's strategy is fundamentally different from the slow, durable approach of terrestrial forests. Speed, flexibility, and regeneration replace strength, rigidity, and persistence.

Growing Fast in a Race for Light

Where trees grow centimeters per year, giant kelp grows centimeters per hour. This velocity requires constant nutrient supply — which is why kelp forests exist only where upwelling or cold currents deliver fertility.

The tradeoff: kelp tissue is metabolically expensive and not built to last. Individual fronds live only 6-9 months. The forest persists not through durability but through constant regeneration — the kelp equivalent of a rainforest that regrows every year.

Flexibility Over Strength

A rigid structure would shatter in ocean surge. Kelp solves this by bending — stipes flex with currents, blades stream in the flow. The pneumatocysts provide just enough buoyancy to keep the canopy at the surface without fighting the water's movement.

This flexibility extends to the holdfast. Rather than a single deep root, the holdfast spreads across rock surface, distributing attachment points. It's harder to peel off than to pull out.

A Two-Stage Life Cycle

Kelp reproduction involves two dramatically different life stages:

Sporophyte → the giant kelp we see, releasing microscopic spores

Gametophyte → a nearly invisible filamentous stage (often just a few cells) that produces eggs and sperm

Spores settle, grow into gametophytes, reproduce sexually, and the fertilized egg becomes a new sporophyte. The microscopic gametophyte stage is often the bottleneck for recovery — it requires specific light, temperature, and substrate conditions that may not exist even when the water looks favorable for adult kelp. This hidden life stage explains why kelp forests can be slow to return after disturbance.

Outgrowing the Grazers

Kelp grows from the base of blades, not the tips. Grazers eating blade tips don't kill the growth zone — the kelp can regrow faster than it's consumed, as long as grazing pressure isn't overwhelming.

When urchin populations explode, this defense fails. Urchins don't just graze tips — they attack holdfasts, severing the anchor and sending the entire kelp drifting to die. The strategy that works against moderate grazing collapses against a population outbreak.

Check Understanding

Direct heat stress does occur—kelp has optimal temperature range of 8-20°C and suffers above this. But the PRIMARY mechanism is more insidious: ocean warming strengthens thermal stratification. Warm surface water becomes less dense and forms a stable layer that doesn't mix with cold, nutrient-rich deep water. This reduces upwelling—the process that brings nutrients to the surface. Kelp needs constant nutrient supply (nitrate, phosphate) to sustain its extraordinary growth. Without upwelling, kelp becomes nutrient-starved even if water temperature is survivable. This explains why kelp forests decline even in marine heatwaves that don't exceed lethal temperatures. The 2014-2016 "Blob" marine heatwave devastated California kelp through stratification-driven nutrient starvation.

Exactly right. Ocean warming strengthens thermal stratification—warm surface water becomes less dense and forms a stable layer that resists mixing with cold, nutrient-rich deep water below. This reduces upwelling, the process that brings nitrates and phosphates to the surface. Kelp needs constant nutrient supply to fuel its extraordinary growth (up to 60cm/day). Without upwelling, kelp becomes nutrient-starved even if temperature remains technically survivable. The kelp can't photosynthesize efficiently without nitrogen for proteins and enzymes. This explains why kelp forests decline even in marine heatwaves that don't exceed lethal temperatures. The 2014-2016 Pacific "Blob" marine heatwave devastated California kelp through this mechanism—stratification starved kelp of nutrients, weakening it and making it vulnerable to other stressors like urchin grazing.

Warming does increase some kelp diseases and pest outbreaks. But the PRIMARY mechanism is ocean stratification. Warm surface water becomes less dense and forms a stable layer that doesn't mix with cold, nutrient-rich deep water. This reduces upwelling—the process bringing nutrients to the surface. Kelp needs constant nutrient supply (nitrate, phosphate) to sustain extraordinary growth. Without upwelling, kelp becomes nutrient-starved even if temperature is survivable and disease is absent. The 2014-2016 Pacific "Blob" marine heatwave devastated California kelp primarily through nutrient starvation, not disease. Weakened, nutrient-starved kelp is then MORE vulnerable to disease, creating a cascade of impacts. But the root cause is stratification-driven nutrient limitation.

Strong storms do tear kelp from substrate, especially weakened plants. But the PRIMARY mechanism of warming damage is ocean stratification. Warm surface water becomes less dense and forms a stable layer that resists mixing with cold, nutrient-rich deep water below. This reduces upwelling—the process bringing nutrients to the surface. Kelp needs constant nutrient supply to sustain its extraordinary growth (up to 60cm/day). Without upwelling, kelp becomes nutrient-starved even without storm damage. The 2014-2016 Pacific "Blob" marine heatwave devastated California kelp primarily through stratification-driven nutrient starvation. Weakened, starved kelp is then MORE vulnerable to storm damage, creating a cascade. But the root cause is nutrient limitation from reduced upwelling.

Under Pressure

Kelp forests face a convergence of threats — warming water, predator loss, and the stable alternative state of urchin barrens that resists recovery.

Kelp requires cold water. Marine heatwaves — now more frequent and intense — push temperatures beyond kelp's tolerance. The 2014-2016 "Blob" in the northeastern Pacific was a mass of warm water that killed kelp forests from California to Alaska.

Many forests haven't recovered. Warming isn't just acute events — it's a chronic shift pushing kelp's range poleward and squeezing forests from their southern edges.

Marine heatwaves are a Heat Flow phenomenon — the ocean absorbing excess atmospheric warmth, then releasing it in concentrated bursts. Kelp forests, adapted to cold water, have no way to acclimate when temperatures spike beyond their tolerance.

The loss of keystone predators tips the balance toward grazers. In California, the combination of sea star wasting disease (which killed sunflower sea stars) and marine heatwaves (which stressed kelp) allowed purple urchin populations to explode.

Over 90% of Northern California's bull kelp forests converted to urchin barrens between 2014-2019.

Once established, urchin barrens are stable. Urchins can survive for years in a "zombie" state, eating almost nothing, waiting for kelp to return — then devouring it before it can establish. Breaking this cycle requires predator recovery or active urchin removal. The barren is a stable alternative state, not a temporary phase.

Other Pressures

Pollution and sedimentation: Coastal runoff carries sediment that smothers young kelp and reduces light. Nutrient pollution can paradoxically harm kelp by promoting epiphytic algae that overgrow blades — shading them out.

Climate trajectory: As oceans warm, kelp forests are expected to contract toward the poles. Southern range edges are already retreating; northern populations may expand if substrate and nutrients allow. The geography of kelp is shifting — a slow-motion migration that will reshape temperate coastlines over coming decades.

The collapse of kelp forests isn't irreversible — but recovery requires active intervention. Researchers and conservation groups are pioneering restoration techniques that address both the symptoms (urchin overpopulation) and underlying causes (predator loss, warming).

Kelp aquaculture is also expanding — farming kelp for food, animal feed, biofuels, and carbon credits. While farmed kelp isn't a wild forest, it may reduce pressure on wild populations and provide ecosystem services in degraded areas.

Active restoration projects: The Bay Foundation (California), Reef Check, The Nature Conservancy, Kelp Forest Alliance

Knowledge Check

Validate your understanding of kelp forest ecosystems

Why Kelp Forests Matter

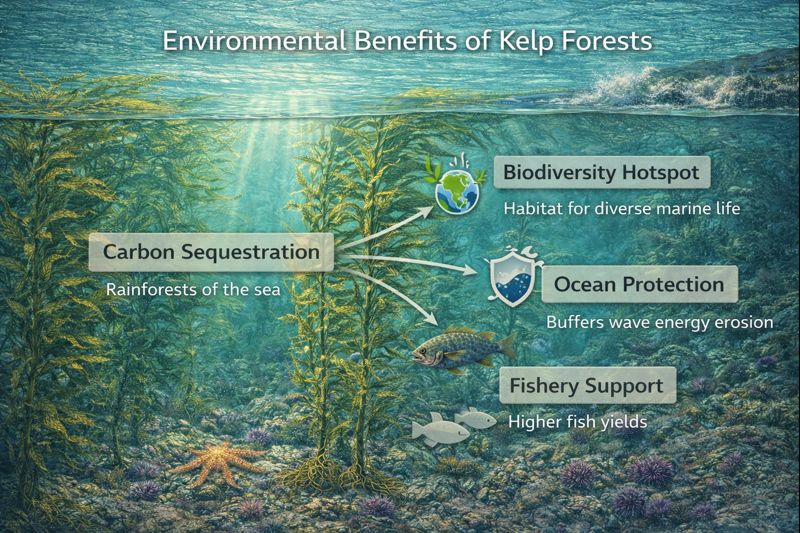

Biodiversity: A single kelp forest can support over 800 species — fish, invertebrates, marine mammals, seabirds. They're biodiversity hotspots of the temperate ocean, rivaling coral reefs in species density.

Carbon sequestration: Kelp forests fix carbon at rates comparable to terrestrial forests. Some of this carbon is exported to deep water as drift kelp and detritus, potentially sequestered for centuries. "Blue carbon" from kelp may be a significant — and undervalued — climate service, though quantifying long-term sequestration remains an active area of research (not all exported carbon is permanently stored).

Fisheries: Kelp forests are nurseries and feeding grounds for commercially important species — rockfish, lingcod, abalone, sea urchins (themselves harvested), lobster. Healthy forests support healthy fisheries; degraded forests mean collapsed catches.

Coastal protection: Kelp canopies dampen wave energy, reducing erosion. They're living breakwaters — coastal infrastructure that builds itself.

Cultural significance: For Indigenous peoples of Pacific coastlines, kelp forests have provided food, materials, and cultural identity for thousands of years. They're not just ecosystems — they're ancestral places.

In a warming ocean, kelp forests create local cool-water refugia. The canopy shades the seafloor; evaporative cooling at the surface can reduce temperatures by 1-2°C. Species retreating from warming may find temporary shelter in kelp — if the forests themselves survive.

Sources: Estes & Palmisano, Science, 1974; Rogers-Bennett & Catton, Scientific Reports, 2019; Krumhansl et al., PNAS, 2016

Systems Connection

Kelp forests exist at the intersection of flows — where cold water, nutrient upwelling, and rocky coastlines converge. Remove any element and the forest cannot persist.

What You've Learned

- Kelp forests solve the "structural paradox" through flexibility, buoyancy, and speed — not rigidity and persistence

- They're the ecological inverse of coral reefs: cold, nutrient-rich, turbulent conditions vs. warm, nutrient-poor, stable

- The sea otter → urchin → kelp cascade is the textbook example of keystone species and trophic control

- Urchin barrens are a stable alternative state — once established, they resist kelp recovery

- Marine heatwaves and predator loss have collapsed >90% of some kelp forest regions

- Kelp forests provide carbon sequestration, fisheries support, coastal protection, and climate refugia